IX

Advanced Theory

Sensitivity and Selectivity

IX

Advanced Theory

Sensitivity and Selectivity

The Sumarah method centers on learning how not to

avoid reality and how to receive reality more

directly. This entails a gradual increase in

awareness or "sensitivity" (peka) and in

understanding or "selectivity" (pilah) that

together bring an advance in "consciousness" (kesadaran),

the combination of these two tools. Increases in

sensitivity and selectivity are accompanied by an

actual boost in perceptual intake. This is a long

process, which begins as an intellectual intention

and carries on through various stages of

decreasing ego separation and increasing

consciousness until it arrives at "surrender" (sumarah).

The practice is a gradual one of expanding

awareness through meditation and then allowing

understanding to catch up and work itself into the

expanded awareness. This rising awareness is what

is called "sensitivity," and reflects the accurate

reception of stimuli that are coming in. The

increased understanding that arises out of

discrimating and identifying the nature of the

increased reception is called "selectivity". These

two functions are closely tied together and their

basic relationship is expressed in the following:

Thought sometimes gets misled, doesn't it? But that's the way it is. Because of that our study here is to make rasa sensitive first, and then you can be as selective as you need to be, as long as your rasa is sensitive first. When you haven't practiced this, the head starts analyzing and rasa gets lost. So you just have to follow the process. (Grogol 6/1/79)

The first stage of the process of increasing sensitivity and selectivity is termed luyut. Luyut is a pleasant, drifting, semi-conscious sensation that looks and feels like a light sleep. This state is experienced when the amount of stimuli ingested (sensitivity) exceeds the ego's responsive capacity (selectivity). Because the ego is unable to process all of the stimuli it is exposed to, it loses consciousness and falls into the drifting associations of luyut. The process is analogous to the eye when suddenly presented with a bright light, when it automatically narrows and the pupil contracts and prepares for the new situation.

Luyut is your limit. It's the limit of your ability to be aware. Later it will change again. Later the luyut will start farther along, in that you will have deepened your consciousness. Then when you reach the same place again, it won't catch you unawares. But when you go still deeper, luyut will come again. In the past, before you had got this far you would have lost consciousness, but not now. In the future, after you've experienced this a number of times, you won't lose consciousness. That's where progress comes into it. (Grogol 6/1/79)

The body is a collection of sensory responses that

reflect the flow of information. When sensitivity

exceeds the ego's capacity to process the

information and rasa encountered (whether

it be too painful, confusing, unusual or

whatever), the information and the experience

connected with it are placed "on hold." These

unassimilated and unprocessed experiences remain

rather like unwelcome guests sitting in the hall:

as long as they are not received, that door, that

sense, that linkage with existence cannot be used

and the information it contains is not available.

In the luyut stage of this process, those

senses are forced open, the ego falls into a light

sleep, beginning the process of absorbing the

information that brought on the snooze. The second

stage is characterized by strong emotion and

especially anger, depression, anxiety and

confusion. This is when the ego responds to the

new material coming through the previously blocked

portal, assimilating this new material and

allowing the sense to remain open. In the third

stage, the ego attains selectivity by completing

its understanding of this material and making its

adjustment to the new information and perspective

involved in it. Then everything calms down and the

process can start over again.

A more dramatic example of this process comes when

you fall in love. First you go through the dreamy,

focused haze of love's high voltage luyut,

followed by the violent emotional swings and

opinion shifts of the process of assimilating and

identifying what the new feeling means and the

worldview it implies. If your love survives this

storm and reaches the calmer waters of mutual

acceptance, the process can complete itself with a

return to seeing your beloved clearly and calmly

in a world transfigured by the added sense the

love brought in.

This process is repeated over and over, and, bit

by bit, small increments of experience are entered

by consciousness while sensitivity and selectivity

increase. The repressed material unearthed in the

second stage of this process is often of riveting

interest to the ego since it defined its limits

and the tone of its worldview. However, the idea

is not to dwell on the stored confusion this

cleansing process brings out, though it must

necessarily be accepted and understood.

When someone starts the Sumarah practice, the

luyut process typically takes a few weeks,

meaning a few meditations. It might take a few

months to work through the whole process in adding

an increment of sensitivity together with its

accompanying selectivity. However, a great deal of

variation is possible. This is especially true at

first. One man said he spent his first seven years

of meditation snoozing in luyut. A

connection is drawn between the difficulty of the

material to be absorbed and the length of time

required for the process. In this case the man was

suffering from distress that retarded the process.

As one becomes more experienced in Sumarah

practice, the process becomes subtler, quicker and

less disruptive.

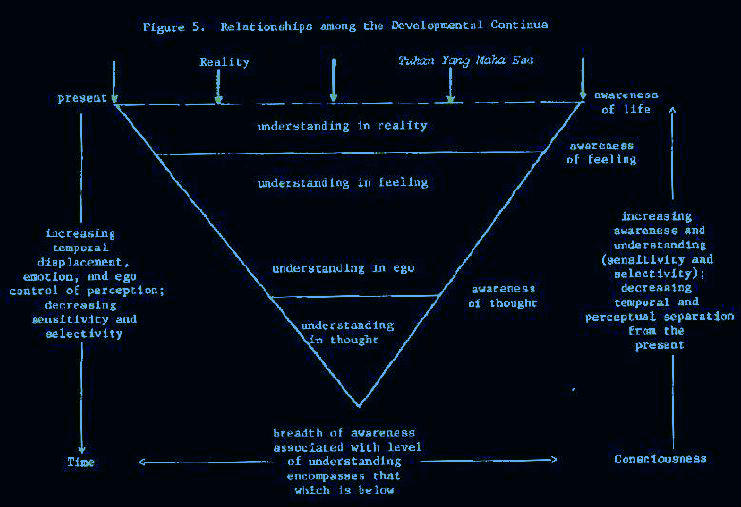

There are two continua that show the development

of sensitivity and selectivity and the

relationship between them. The first is the

selectivity or understanding continuum and the

first level of understanding is ngerti, an

intellectual grasp of something that is limited to

thought. For example, you realize you that smoking

is not good for your health and note that you

would like to stop in passing. The second level is

ngakoni, a kind of confession and deeper

understanding that encompasses the ego. Here you

admit that you do not know why you are unable to

stop smoking, even though there are so many good

reasons to; you come to feel the action as

independent of your decision and seen it in more

depth. The third level, ngrumangsani, is

understanding based on rasa and sees the

issue in a more accepting context. You realize

that smoking is not just your problem and that it

is a general social problem that you are a part

of. You start looking to others to find a way to

control or at least understand your compulsion.

Nglengganani is the fourth level when

understanding corresponds to rasa murni and

provokes no separation from experience or from

reality itself. You understand that smoking has

positive and negative aspects and that sometimes

it can serve a physical, social and psychological

function, and that it is proper if there is a

real, natural call for it, but not for personal

pleasure or comfort. To see the behavior clearly

you must accept it. Up to this point,

contemplating the issue had induced a kind of

confusion that pulled you out of the present;

thinking about it and either justifying or

condemning it takes you down through your

arguments and reasons, placing you in the past and

rerunning your feelings and understandings about

it. The incident has not yet been brought out into

the open, confronted and released. In the case of

ngerti this discontinuity may be brief and

slight, but in ngakoni and ngrumangsani

the disruption can be considerable. In

nglengganani the understanding returns to the

present and is seen in its real perspective --

neither denied nor over-emphasized. This completes

the process of confronting and releasing the

experience.

Figure 1.

Selectivity Continuum

Increasing

Selectivity or Understanding

ngerti understanding in thought

ngakoni understanding in ego (confession)

ngrumangsani understanding in rasa (feeling)

nglengganani understanding in rasa murni (reality)

The second continuum concerns selectivity, the

active component of experience, when you try to

understand and fit your responses into the real

situation, sensitivity is the passive component of

experience; it is what you receive and can be

aware of rather in the manner that a camera

responds when the lens shutter is opened. However,

the two are closely tied together and each is both

complemented and limited by the other. People

generally start the practice in a tangle of

understanding and awareness and the relationship

between the two aspects of consciousness is not

apparent. The first step in the development

process is to pry sensitivity and selectivity

apart. This separation is a mechanical process

that results from practicing the meditation and

bringing enough energy out of you thinking to make

its limited scope and power apparent. The

watershed in the development of consciousness is

crossed with the attainmnt ent of "awareness in

thought" (eling ing pikir), which comes

when sufficient awareness is in the present and

spread throughout the body so as to give thought a

delimited perspective. Before this stage thought

seems to be the whole of experience and the

experiencer moves from one thought to the next

seeking meaning and pleasure. When "awareness in

thought" arises, thought's limited scope and

impact on reality is grasped and thought's

previous importance is now tempered by this

awareness. As a result, you start to look for

meaning and pleasure more in your experience

itself and less in thinking about it. "Awareness

of thought" encompasses the ngerti level of

understanding.

The sensitivity continuum's second level

"awareness in feeling" (eling ing rasa),

when enough energy is released from ego processes

though relaxation and acceptance to put feeling in

a delimited perspective. Previous to this level,

you necessarily feel bound to the rises and falls

of emotion and feeling. You try to manage your

experience the way a person on the roller-coaster

controls his fear by pretending the ride is over.

With "awareness in thought" you recognize that

thought is just a tool in the larger frame of

experience but the limited nature of feeling is

not yet apparent. Feeling is encompassed by

awareness when its necessarily transient nature is

appreciated and accepted; at this point you become

conscious of the informational rather than the

diversional importance of feeling's rises and

falls. The variations of affective experience are

seen as lessons connected with the process of

maturation rather than being judged by the

hedonistic criteria generally used up to this

point. However, "awareness of feeling" is confined

to the calmer areas of experience: when strong

emotion or desire is experienced this will exceed

the limits of the range of this awareness. An

effort to return to this calm and broad

perspective will eventually come. This will

involve an increase in consciousness as the new

feeling is accepted and brought into an open

perspective where it can be seen more clearly and

acted on more effectively. "Awareness of feeling"

encompasses ngerti, ngakoni and

ngrumangsani levels of understanding. Contact

with reality begins at this level of awareness,

but the contact is subtly colored and distorted by

a still struggling ego and fear of not controlling

your experience.

Next on the sensitivity continuum is "awareness of

life" (eling ing jiwa). Jiwa refers

to roughly the same holistic concatenation of

desires, feelings, emotions, thoughts and physical

sensations associated with human experience as

dasein or epoche in existential

psychology and phenomenology. "Awareness of life"

comes when the whole of experience is encompassed

within an excepting and accurate state of

consciousness. Using the camera analysis again,

the filtering lenses have now been removed; you

open without any of the defensive perceptual

selection that had been present previously. While

consciousness was restricted to a certain range of

potential experience in "awareness of feeling," in

"awareness of life" the ego withdraws from active

participation in defining its state and takes

whatever comes to it. You no longer reach out

toward pleasure or shrink away from confusion; if

they come, so be it. When "awareness of life" is

reached, the amount of perspective derived from

this sweeping panorama of being contains the

desires, feelings and thoughts in a generally

quiet and comprehensive frame. More intense

responses are still present but they are generally

brought out into the open rather quickly,

confronted for what they are and released. The

fear of not being in control gives way to an

acceptance of the fact that you never really were.

Up to this point in the stages of development, the

desires contain consciousness. With "awareness of

life" consciousness finally learns to participate

in the desires. "Awareness of life" encompasses

the nglengganani level of understanding and

the two together comprise the active and passive

aspects of rasa murni. Nglengganani

is understanding that is not separated from

reality in the present. "Awareness of life" is the

direct, uncensored reception of what is here now.

Figure 2.

Sensitivity Continuum

Increasing

Sensitivity or Awareness

eling ing pikir awareness of thought

eling ing rasa awareness of rasa (feeling)

eling ing jiwa awareness of rasa murni (life)

Flexibility

With time

and practice consciousness gradually gets stabler

and the general tone of being calms; however,

states of awareness are not fixed: they are part

of the process of receiving reality. Situations

constantly arise that require new applications of

the process of receiving and responding and this

constant demand for expanding consciousness and

self-criticism is compared to bathing: "So you

bathe today. Does that mean that you won't need to

bathe again tomorrow? It's a continual process.

You keep getting dirty, so you keep needing baths.

It's the same way with this." Flexibility is the

key to facilitating this process and refers to

sensitivity and selectivity's ability to cooperate

and work together. Increasing consciousness is a

process that cannot be circumvented or rushed, but

it can be aided by familiarity, relaxation and

acceptance.

Two

stategies are used to help in attuning and

increasing flexibility. The first is "Studying

being able to accept criticism from anyone and

anything" (Ajar gelem deelingke sapa lan apa

wae). This is initially a rather philosophical

position used to maintain perspective, that

becomes a habitual attitude over time.

Understandings are limited by nature and are

constantly in the process of being contradicted

and revised by reality. The quickest way to update

and improve them is to be open to the total source

of criticism: existence itself.

The family

context is generally the richest source of

criticism and instruction, but all other aspects

of life are to be approached in the same way.

Opinions are to be offered with an attitude of

"Maybe I'm right, maybe I'm wrong, but this is

what comes to me." Criticism is received as

something to be resolved by reality, not by

argument. Anger experienced in response to

criticism is confronted in the context of your own

limitations: "Well, am I always right? Is he

always wrong?"

The strategy

in flexibility is coordinating sensitivity and

selectivity and relates to a continuum of

"willingness" (gelem) and "unwillingness" (moh).

Before beginning this process, the character is

made up of powerful, combative elements that

compete in connection with any decision. The

"should" and the "shouldn't" are both represented

by batteries of emotion, argument and other tools

of persuation. Each decision in life (but

especially major ones) affects your total

condition; your experience speaks for or against

it from various perspectives. But the only

reliable place to adjudge and respond to any

situation is the present where the concern itself

is -- not knocking about among contentious

memories. The first step in relaxing and opening

this process to greater sensitivity is, "Making

the unwillingness willing" (Gelemke si moh).

For example, you might force yourself to meditate

and keep yourself relaxed whether you want to be

at the moment or not. When this is done, a kind of

ceasefire is imposed in the battle between the

"should" and the "shouldn't" and the emotional

charge attached to the decision-making process

gradually diminishes.

After your

experience has settled down sufficiently, a second

stage is entered, "Being willing to be unwilling"

(Ngglemi si moh), which means respecting

and "Being in the tools" (Manggon ana ing alate)

connected with unwillingness. Any decision should

be reached in the present; while the

should/shouldn't argument is raging, it drowns out

all but the least subtle aspects of your present

situation. The first step suspends this argument

and inceases sensitivity, and then the second

places attention directly in the "tools", the

actual responses to stimuli and fosters

selectivity. Both "willingness" and

"unwillingness" are founded in experience, and now

attention is directed toward appreciating the

rightful aspects of "unwillingness."

The third

stage is "Willingness along with unwillingness" (Moh

wi gelem) and its aim is to bring balance to

"willingness" and "unwillingness" in their real

context. This stage is connected with "Separation

from the tools" (Pisah karo alat) and

involves a continual study of the actual

informational content and import of your

responses, which gradually can become more and

more subtle and refined. The emphasis is both on

receiving the responses accurately (sensitivity)

and on discerning their significance

(selectivity). The body is an enormous collection

of informational responses. The first two stages

provide the basic method for receiving and sorting

out this material; now the method is applied to

the great mass of undifferentiated information

that makes us up and gradually subtler and subtler

responses are separated out, received and

understood. This is when sensitivity and

selectivity learn to work together smoothly.

Understanding becomes less emotionally entrenched

in being right; as a result, when understanding is

contradicted by experience, it can be registered

and whatever adjustment may be needed can be made

more quickly. Similarly, since selectivity is more

responsive to contradictions arising in

sensitivity, sensitivity is not forced to amplify

and distort these contradictions as much in order

to get them recognized. The process gets

increasingly refined and operates more quickly as

selectivity learns to stay close to sensitivity

and experience itself. These are the simple

applied mechanics of the opening process.

The fourth

and final stage of this process is, "Can't be

willing; can't be unwilling" (Moh ora isa,

gelem ora isa) and is connected with "Uniting

with the tools" (Manunggal karo alat).

Sensitivity and selectivity become one, united in

the real present (rasa murni); the ego

ceases as a separated entity withdrawn from actual

experience and surrender (sumarah) begins.

The "can't be" wording refers to the lack of any

separated will in surrender and unity of

experience -- attention now goes into being here

and responding as reality would have it. Responses

are direct and spontaneous reactions to the

situation and contain no personal input and hence

no "willingness" or "unwillingness."

The fourth

stage is the basis of Sumarah's leadership

practice. Leadership requires this openness to

reality and the information that comes

spontaneously out of it. A leader is not a person

but a relationship with reality and Tuhan Yang

Maha Esa.

Figure 3.

The Flexibility Continuum

Increasing

Spontaneity

Gelemke si moh. Making the unwillingness willing.

Nggelemi si moh. Being willing to be unwilling.

Moh wi gelem. Willingness along with unwillingness.

Moh ora isa, gelem ora isa. Can't be willing; can't be unwilling.

This

spontaneity sometimes results in responses and

behavior that is clearly understood and sometimes

brings out responses that are a surprise to all

present (including the pamong). This

reflects the nature of spontaneity together with

the limitations of understanding. Sometimes such

unanticipated reactions are later clarified and

sometimes they are not. The following two

incidents illustrate this.

The first

occurred before a meeting. The pamong was

sitting with early arrivals, chatting and waiting

for the rest to come. He saw a woman come in and

suddenly felt he should take her and another woman

aside. He did this without knowing why it felt

proper; it turned out that the two women had had

an argument the previous day that needed to be

talked about. This was an instance when the

reaction was clarified.

In the

second incident the pamong was going to an evening

meeting with me on the back of his motorcycle.

Suddenly he felt a "change" and did not know if it

was proper for him to go to the meeting or if

there was something else that he should do. He

stopped at another leader's house and asked for an

opinion. The two sat there, looking a little like

hounds sniffing the rasa breeze and trying

to figure out what this new scent was. The source

of this one never came clear and the matter was

dropped unresolved. They talked for awhile and we

eventually went on to the meeting together.

Spontaneity's importance in defining behavior is

not restricted to leaders. As a person gains

greater sensitivity, a simple ethic is presented,

"When something inside you tells you not to do

something, don't do it. When nothing inside you

objects, then it's all right." For example, doing

business and making a profit are all right up to a

certain point. After that your feelings will tell

you that you are taking advantage of your

neighbors and should charge less.

This

principle applies to all behavior, not only to

situations where there is a clear reason for the

negative reaction. If you want to visit a friend

and something tells you not to, you should not go.

Here the negative feeling may mean any number of

things, with one possibility simply being that the

friend is not home. This is the way the

information based on increased sensitivity to

rasa and reality is brought into everyday

life.

The desire

to do what is right is highlighted by a

distinction between proper etiquette behavior (tata

krama) and proper behavior (aturan).

Etiquette observes the prescribed forms in this

tradition rich culture; however, such socially

correct behavior can be empty and inappropriate in

a real sense. Proper behavior conforms to the

demands of reality and is correct not in relation

to some abstract schema or criterion but in

relation to the real context.

The conflict

between the two codes is seen in the way leaders

behave at meetings. Proper etiquette demands

proper speech, observance of levels, of tone and

vocabulary, but this propriety can interfere with

communication -- a leader's role sometimes demands

more flexibility and color. This is not to

challenge etiquette's importance in some

situations but to assert the importance of letting

the situation define the behavior that is most

appropriate. For example, Suwondo can be raucous

or refined depending on whom he is talking to and

the demands of communication. As we will see in

one of the cases, proficiency in the art of

communication is an art acquired through

experience and practice -- trial and error.

Ranks or Levels of Attainment

The terms

and continua presented up to this point are quite

specific and are used to describe a person's

condition at a particular time. "Selectivity" is

generally chosen to give an idea of how things are

right now. Consciousness can go up and down. It

might start the day calmly in ngrumangsani

and then dip into ngerti and then in a

moment of acceptance and contemplation, climb back

up to ngakoni.

Summarizing

the material above, a person's consciousness at

any given time reflects his/her relationship with

that particular environment as well as whatever

might be arising out of the understanding and

sensitivity/selectivity process. In addition to

changes that take place over time in a linear

fashion from moment to moment and situation to

situation, changes also come in association with a

particular subject as consciousness progresses

through the stages of ngerti, ngakoni,

ngrumangsani and completes itself in

nglengganani.

However,

there is also a broader continuum that depicts a

person's general condition or level of attainment.

During its history Sumarah has gone through

various periods and emphases. Nowadays each leader

is free to use whatever explanations and

illustrations come to him, and there is a great

deal of variation. The following discussion of

ranks or levels of attainment is somewhat

particular to Central Java and comes from one of

our great masters, Suhardo, a founding member of

Sumarah.

On the path

to total surrender, the first stage or rank (martabat)

is "intention" (niyat), an understanding in

thought (ngerti) when a person decides he

wants to learn the practice and open to reality.

This level is an intellectual commitment rather

like deciding to attend school and get an

education.

With

training and practice the intention becomes firmer

and the experience allows understanding to expand

and include the ego (ngakoni). The person's

experience confirms his initial intention and the

intention turns into "resolve" (tekad).

Resolve is still an expression of the ego, though

the ego is now more unified and confident about

what it is doing.

With

continued practice, this resolve deepens, becoming

more accepting, less founded on personal interest

and more interested in giving back service for the

boon received in the practice. This is where the

walls of the ego come down and interaction with

reality begins. It is here in "faith" or

"conviction" (iman) as well that the true

practice of Sumarah starts.

Faith is

sub-divided into three levels. The first is "young

faith" (iman muda), when awareness settles

into the heart area and is accompanied by a

sensation of coolness or relief. The willingness

to open to and accept reality is present but still

held back by lack of practice.

The next

level is "mature faith" (iman dewasa), when

consciousness of reality reaches a sense of a

strong and comforting force or power; the first

uncensored reception of reality and Tuhan Yang

Maha Esa. This comes as a self-evident visual

and physical glow of relaxed acceptance.

Faith's

third level is "true faith" (iman bulat),

ego's final stage of participation before quieting

in surrender. True faith is characterized by

stability and calm acceptance, and is firmly

established in "awareness of feeling." The

stability allows the release of repressed

experiential and sensory material formerly

occluded by ego activity. An active ego takes the

energy from these occluded senses and invests it

in its own purposes. Stability and a quieting of

ego processes gradually allow energy to return to

these subtle sources of information and they open

up again. This is where the "true teacher" (guru

sejati) arises and it is at this point that

the task of serving "natural law" (purba wasesa)

begins in earnest as a moment-to-moment

occupation. The reception of reality assumes an

active rather than a passive aspect as you learn

to receive the demands of reality cleanly and in

the present. Gathering the consciousness necessary

to enter into surrender takes time and this is

what takes place during "true faith."

After the

levels of faith (iman), where ego processes

are increasingly refined, stabilized and relaxed,

come the levels of surrender (sumarah)

where ego processes are transcended and direct

congress with reality begins. The first level of

surrender (sumarah 1) involves direct

awareness of rasa murni as consciousness moves up

to the border with Tuhan Yang Maha Esa; an

expansive, engulfing experience accompanies this

initial experience of the reality of being with

God. In surrender the Will of Tuhan Yang Maha

Esa is experienced and carried out directly.

The "true teacher" is eventually transcended and

comes within consciousness. In the higher levels

of surrender, more and more direct contact with

being and Tuhan Yang Maha Esa come and

awareness goes on beyond "awareness of life" (eling

ing jiwa) to a "true" or "pure awareness" (sejatining

eling). We do not talk about these levels very

much because effective description is impossible

without experience. In fact, all of these

mechanics of the opening process are essentially

meaningless without their application. The levels

of surrender stretch on upward as far as the

service and consciousness of those who do the

practice have reached in distinguishable and

verifiable experience. For example, Suhardo's rank

of surrender is "sumarah" followed by an

enormous number.

During

Sumarah's early history, rank was observed quite

formally and mature members met separately from

new members. Nowadays all meetings except the

leader training meeting are open; rank is quietly

observed but is no longer emphasized.

Figure 4. Ranks or Levels of Attainment

niyat intention

tekad resolve (ego)

iman muda young faith

iman dewasa mature faith

iman bulat true faith

sumarah levels of surrender

The levels

of attainment are also related to "chakra." Three

chakra are referred to in Sumarah; they are

sometimes called by their Sufi (Arabic) names but

more commonly by their Hindu-based Javanese names.

The first is the lower chakra in the lower abdomen

and genital region, which is bait al muqaddas in

Arabic and janaloka in Javanese. This chakra is

where the energy for "resolve" (tekad)

comes from and is especially connected with "will"

and "determination."

The middle

chakra in the heart area is called bait al

muharam or hendraloka. This center is

connected with rasa and the "faith" (iman)

stage of development. The heart chakra is the gate

to sensitivity and Sumarah is sometimes said to

begin only when this chakra is entered.

The upper

chakra in the head is called bait al makmur

or guruloka, and it the center where

sensitivity and selectivity meet, eventually

yielding the surrender stage of development.

Development

is progressive and cumulative, a process of

cleansing or clearing the accumulated unreleased

experiential material out of these energy channels

and opening them up. After a chakra center is

cleansed, the spirit and energy that were trapped

in the confusion there can now move up into the

next area needing attention -- the next center of

confusion. Practitioners are advised to try to

clear the lower center before moving up to the

heart chakra. This can help to avoid a great deal

of emotional turmoil. However, they are much more

strongly counselled not to force the "surrender"

stage of development. Pushing energy up into an

uncleaned chakra is like shining a light through

the dirt on a window, and in the head chakra this

energy can spark disruptive reactions as the

energy rocks the tenuous balance of thought and

emotion before they have sorted themselves out.

Figure 5. Chakra (Triloka)

English Javanese Arabic Association

lower chakra janaloka bait al muqaddas resolve

(genital)middle chakra hendraloka bait al muharam faith

(heart)upper chakra guruloka bait al makmur surrender

(head)

Consciousness Maintenance Techniques

Sumarah

practice includes a number of

consciousness-assisting or maintaining techniques.

They are used to pull one out of distractions and

disturbances to the daily meditation and to assist

in attaining a more accepting and open reception

of reality from moment to moment.

The first is

breathing, which can give you an excellent monitor

on the your physical and spiritual state.

Breathing provides you with an idea of what you

are doing in much the same way that heart rate and

blood pressure do and the Javanese tradition

includes a kind of biofeedback orientation in

connection with it.

The levels of breathing are napas, anapas, tan-napas and nupus. In napas the breathing is still coarse and unregulated. In anapas it is a bit more refined but actually still pretty coarse. When you get to tan-napas it starts getting refined, and then comes nupus. Napas, anapas, tan-napas and nupus are connected with the working of the heart and lungs. When breathing is coarse, the working of the lungs is unregulated, the heart beat too heavy and the circulation of the blood is too rapid and unregulated. Everything is working in excess. But if this can be relaxed, if the nerves can be relaxed, the heart isn't forced to work so hard and you actually have more endurance. But when the heart is forced to beat heavily, like when you get mad and your heart pounds, you'll get tired fast. This is usually not paid attention to. (Keratonan 4/10/80)

Sumarah counsels, but does not stress, continuous attention to refining your breathing. This tool is used primarily in identifying influences on your experience through the way your breathing varies from moment to moment. The practice also emphasizes using breathing to regulate and control sharp emotional responses.

Actually the sexual desire that comes out like that is basically just a desire, and all desires burn up energy. The amount of energy generated depends on oxygen. When oxygen use is moderate it's no problem. But when combustion gets excessive to supply the call for energy, that causes the heart to beat faster and influences body heat. At the same time it changes and strengthens the desire. Because of this, when you want to lessen a desire, exhale completely; do that in order to balance the energy and the desire so that it's not too strong. (Grogol 6/1/79)

A pamong will at times feign

anger, taking a huge breath and holding it. Then

he tries to maintain the angry stance while

exhaling completely, demonstrating that anger is

hard to keep up without a special supply of

oxygen. If the anger reflects an ego perspective,

it needs ego-produced energy to exist and will

disappear when you relax.

Another

common technique is repeating the name of God,

"Allah." Mantras as such are not used in Sumarah,

but "Allah" is often called out during a

meditation. The energy and associations of the

word assist in the acceptance and reception of

reality and help pull people out of their

self-centered frames of reference. This device can

also used when something disturbs your daily

meditation; it can be said aloud or silently.

Another

tactic is stopping to check your disposition and

looking to see where your actions and desires are

coming from at that moment. This is especially

advocated during conversations, and particularly

for those who tend to get emotionally involved in

what they are saying. The pause is used to note

the emotion or influences and try to calm down.

Still

another technique is a prayer for guidance during

difficult or indecisive moments. The prayer has a

form like, "What would it be best for me to do?" (Kedahipun

kula kados pundi?) or "What is Thy Will?" (Panjenengan

kersa menopo?) This is a powerful tool for

opening yourself to the situation, putting it into

a proper perspective and receiving it as

accurately as possible. This open sense then

becomes the basis for seeking a solution

eventually, putting the problem in as real a frame

as possible.

Another

tactic is advocated when someone does something

that seems silly or contemptible and involves a

pause followed by focusing on the concept

"respect" (kurmat or hormat). This

concept has a number of different levels and

aspects. The first and most pragmatic is that open

reception demands it; letting things be as they

are is a mechanical aspect of reception itself.

For example, when you are listening to someone

talk and find what they are saying foolish, the

tendency is to pull back from the situation and

either stop listening or prepare a rebuttal. In

either case you are no longer here. Sumarah holds

that being in the present takes precedence over

such discomfort and being here requires the

acceptance of all that are here with you. The

scornful denial of anyone or anything's right to

exist impoverishes your experience by blocking out

that part of reality. This is also senseless,

because whatever it is, it does in fact exist.

This is sometimes hard, but a related point is

that any program for coping with your situation

can only be responsible if you are seeing it

clearly, not denying parts of it.

The concept

of respect goes deeper to tepa slira. All

human beings are fundamentally alike and we all

start off as infants in the same wide-open

condition of rasa murni. Life changes this

initial state but a measure of commonalty is seen:

that which affects A in a given way would probably

have a similar affect on B. So while it may be

difficult to respect a person at a given time in

his life, it is impossible not to respect the

rasa murni condition of the struggling infant

that underlies him and is trying to return home to

openness.

At a still

deeper level respect relates to the "true

teacher," who is at the base of all our experience

and the personal representation of reality and

Tuhan Yang Maha Esa. Thus, at our essential

level we are all part of the divine. In the story

about Bima's search for the waters of eternal life

in Chapter 6, when Bima meets Dewaruci (the true

teacher) and discovers who he is, he speaks in

high Javanese (krama inggil) with him; he

the only character in the entire epic Bima grants

such respect. Sumarah views this deep feeling of

respect as being required for everyone's inner

nature because, whether they are aware of it or

not, everyone is a part of nature and the divine;

full reception of them requires seeing this aspect

of them as well. This humble respect applies to

yourself as well: your inner being, your soul,

exists beyond your ego just as anyone else's does,

deriving your existence from the totality and

managing the expression of the totality in you.